Pharaoh’s Brick Makers

Israelite construction workers in Egypt

Marek Dospěl May 17, 2022 1 Comments 16557 views

THE PYRAMID OF PHARAOH DJOSER (27th century B.C.E.), in Saqqara, was the first built in stone. Rooted in the tradition of monumental architecture built with mudbricks and light materials, Djoser’s pyramid complex exhibits many features developed for those materials, only “translated” into stone. This includes the pyramid itself, which consists of multiple mastabas (bench-shaped structures) piled on top of each other; hence the nickname, the Step Pyramid. Photo: Xiquinhosilva; CC BY-NC-SA.

Contrary to popular belief, the Bible does not assert that during their sojourn in Egypt the Israelites were involved in building the pyramids. Although fundamental questions remain regarding the presence of Israelites in Egypt and the Exodus—including the dating and scale—it is certain that the most impressive, stone-built pyramids of the Old Kingdom (27th–22nd century B.C.E.) predate the biblical Exodus by hundreds of years. Moreover, there is now plenty of contemporary evidence showing that the pyramids were constructed by indigenous professional builders, not enslaved foreigners.

So what is it the Bible really claims about the Israelites’ forced labor for the Pharaoh? Writing for the Spring 2020 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review, David A. Falk of the Vancouver School of Theology examines the question of Israelites in Egypt and their building activities in his article “Brick by Brick.” Falk scrutinizes the biblical account and looks for the most plausible match in ancient Egyptian architecture.

BRICK MAKING IN EGYPT. Painted on the walls of the Theban tomb of Rakhmire (mid-15th century B.C.E.), who was the Egyptian vizier (or prime minister), these realistic scenes depict slaves manufacturing mudbricks. Included are all stages of brick making (bottom, left to right): fetching of water, kneading of clay, and carrying of moistened clay to brick makers. The top register depicts (right to left): forming of the bricks using a mold, turning of formed bricks out of a mold, and leaving the bricks to dry in the sun. Straw, which is added to the clay mix as opening material, does not appear. Photo: Kairoinfo4u; CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The Book of Exodus makes two basic assertions: prior to the biblical Exodus, the Israelites in Egypt were forced to make mudbricks, and they built “supply cities.” In Exodus 5:6–8, we read: “Pharaoh commanded the taskmasters of the [Israelites], as well as their supervisors, ‘You shall no longer give the people straw to make bricks, as before; let them go and gather straw for themselves. But you shall require of them the same quantity of bricks as they have made previously.’” This makes it clear that the Israelites’ task was to manufacture mudbricks, which is, in less specific terms, further confirmed in Exodus 1:14: “[The Egyptians] made their lives bitter with hard service in mortar and brick and in every kind of field labor.”

WAREHOUSES OF GODS. Belonging to the mortuary temple of Ramesses II at Thebes (13th century B.C.E.), known as Ramesseum, these large mudbrick buildings were designed to store food supplies in an economy built around the cult of a pharaoh. Photo: Public domain.

Exodus 1:11 adds a rather puzzling statement: “They built supply cities, Pithom and Ra’amses, for Pharaoh.” What were these “supply [or “storage”] cities” (‘ārê (ham) miskenôṯ, in Hebrew)? The biblical name Pithom most likely stands for Per-Atum, “Estate of Atum,” which has only tentatively been identified with modern-day Tall al-Maskhutah. Ra’amses must be Per-Ramesses, “Estate of Ramesses,” the new capital of Egypt built by Ramesses II (13th century B.C.E.) near ancient Avaris. Apparently located near to one another, both cities lay in the northeast Nile Delta, where there is abundant historical evidence for West Semitic peoples starting at least in the Middle Bronze Age II (c. 2000–1570 B.C.E.).

Our website, blog and email newsletter are a crucial part of Biblical Archaeology Society‘s nonprofit educational mission

This costs substantial money and resources, but we don’t charge a cent to you to cover any of those expenses.

If you’d like to help make it possible for us to continue Bible History Daily, BiblicalArchaeology.org, and our email newsletter please donate. Even $5 helps:

Falk argues that these two cities cannot properly be described as “storage cities”; the Bible here more likely refers to some enormous mudbrick buildings within these cities. Falk then suggests that the term could denote a series of mudbrick depots or warehouses associated with temples. In Egyptian temples, extensive storage capacities were necessary to provide for daily offerings and the numerous personnel. In the case of royal mortuary temples, it was furthermore critical to assure that a temple would continue operating even after the king’s death.

THE EARLIEST EGYPTIAN ROYALTY chose to be buried at Abydos in southern Egypt. The extensive necropolis at desert’s edge contains royal tombs that predate the first Egyptian dynasty. The most impressive structures at Abydos, however, are the massive mudbrick enclosures identified as funerary sites for the kings of the first and second dynasties (c. 2925–c. 2650 B.C.E.), at the site known today as Shunet el-Zebib. The recessed wall pictured here belongs to the enclosure of King Khasekhemwy (c. 2780 B.C.E.). Photo: Kairoinfo4u; CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Mudbrick architecture in Egypt has a very long tradition going back to the predynastic period and continuing to this day. Starting with Djoser (27th century B.C.E.), Egyptian pharaohs built their tombs and temples in stone, but most other structures continued to be built with sun-dried mudbricks and light materials, such as wood and reed. This was especially true for private houses, royal palaces, and administrative buildings associated with temples. It is therefore very likely that mudbricks manufactured by the Israelites in Egypt were meant for building temple storage facilities or workshops, which is indeed the case with the scene from the tomb of Rakhmire, where an inscription specifies that the workers are “making bricks to build anew the workshops at Karnak.”

For the full analysis of the biblical passages about the Israelite brick makers in Egypt and about the kinds of mudbrick buildings they constructed, read “Brick by Brick,” published in the Spring 2020 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

THE CHRISTIAN NECROPOLIS OF BAGAWAT, in the Kharga Oasis, features some 260 funerary chapels built of mudbricks. Constructed between the fourth and seventh centuries C.E., they are domed, with arcades, columns, and niches decorating their exterior walls. A few chapels boast splendid interior wall paintings. The necropolis is a standing example of the lasting tradition of ancient Egyptian mortuary architecture in unbaked bricks. Photo: Kabaeh49; CC-BY-2.0.

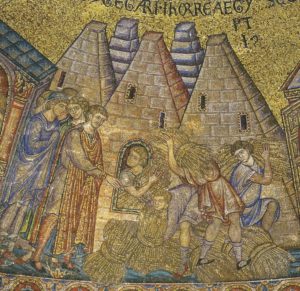

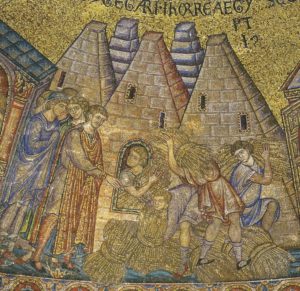

JOSEPH’S GRANARIES. As a side story to the Israelites’ involvement with the Egyptian pyramids, we should correct another false claim. As this mosaic in a cupola of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice demonstrates, medieval Europeans believed that the biblical patriarch Joseph stored up grain (Genesis 41) in the pyramids. Dating to about 1275, this scene includes Joseph standing in front of five pyramid-shaped granaries and giving orders to the workmen collecting the sheaves. Photo: Public domain.

Subscribers: Read the full article “Brick by Brick,” by David A. Falk in the Spring 2020 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

Not a BAS Library or All-Access Member yet? Join today.

Related reading in Bible History Daily:

Did Pharaoh Sheshonq Attack Jerusalem? Shishak, actually Pharaoh Sheshonq I, left his own account of this northern campaign carved into the walls of the Temple of Karnak in Egypt, but he does not mention Jerusalem among the places he conquered.

Ancient Egyptian Beer Vessels Unearthed in Tel Aviv, Israel The excavation, led by Diego Barkan of the IAA, revealed 17 Early Bronze Age I (c. 3500–3100 B.C.E.) pits, in which were found hundreds of sherds from locally produced pots as well as fragments of large ceramic basins used to prepare beer.

Akhenaten and Moses Defying centuries of traditional worship of the Egyptian pantheon, Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten decreed during his reign in the mid-14th century B.C.E. that his subjects were to worship only one god: the sun-disk Aten.

Epilepsy, Tutankhamun and Monotheism Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in 1922 not only revealed the opulence of Egyptian antiquities, it sparked one of the greatest medical and forensic mysteries in human history.

Bronze Age Collapse: Pollen Study Highlights Late Bronze Age Drought During the Late Bronze Age (1500–1200 B.C.E.), the Eastern Mediterranean boasted a flourishing network of grand empires sustaining sophisticated infrastructures, the likes of which the world would not see again for centuries to come