Examining the “spirit of python” in the Bible

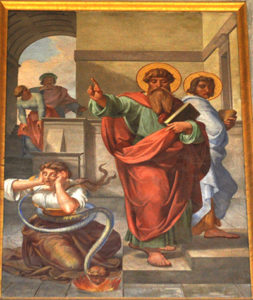

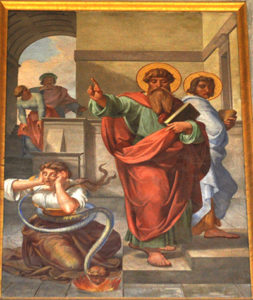

Paul and the Slave Girl. This oil painting shows the apostle Paul casting the “spirit of python” from the slave girl, whom he encounters in Philippi. Based on the episode from Acts 16 in the Bible, the painting dates to c. 1860 and appears outside the Basilica of St. Paul in Rome. Photo: Richard Stracke/CC by-NC-SA 3.0.

According to Greek mythology, the god Apollo killed the massive snake Python at Delphi, Greece. Some traditions claim Python to be the child of the goddess Gaea (Earth), who had a sanctuary at Delphi. Following Apollo’s victory, a temple dedicated to him was set up at the site, which replaced Gaea’s earlier sanctuary and appropriated her oracle. For more than a millennium, people sought the prophecies of Apollo’s famous oracle at Delphi: Pythia, a priestess at the temple, who was said to have the spirit of the god.

Some may be surprised that a passage in the Bible has a connection to Python from Greek mythology. In Acts 16:16–24, the apostle Paul meets a slave girl with a “spirit of python,” who is able to tell the future. John Byron examines this passage in his Biblical Views column “Paul, the Python Girl, and Human Trafficking,” published in the May/June 2019 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

The scene of Paul and the slave girl from Acts 16 is set in Philippi. Paul encounters the unnamed slave girl and eventually exorcises the “spirit of python” from her. This action, which deprives her of her fortune-telling ability, angers her owners and lands Paul and his companion Silas in prison. The full episode reads:

One day, as we were going to the place of prayer, we met a slave-girl who had a spirit of divination and brought her owners a great deal of money by fortune-telling. While she followed Paul and us, she would cry out, “These men are slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim to you a way of salvation.” She kept doing this for many days. But Paul, very much annoyed, turned and said to the spirit, “I order you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her.” And it came out that very hour. But when her owners saw that their hope of making money was gone, they seized Paul and Silas and dragged them into the marketplace before the authorities. When they had brought them before the magistrates, they said, “These men are disturbing our city; they are Jews and are advocating customs that are not lawful for us as Romans to adopt or observe.” The crowd joined in attacking them, and the magistrates had them stripped of their clothing and ordered them to be beaten with rods. After they had given them a severe flogging, they threw them into prison and ordered the jailer to keep them securely. Following these instructions, he put them in the innermost cell and fastened their feet in the stocks. (Acts 16:16–24, NRSV)

Byron clarifies that although many English translations, including the NRSV quoted above, say that the slave girl had a “spirit of divination,” the original Greek says she had a “spirit of python.” This connects her fortune-telling ability to Python from Greek mythology and the oracle at Delphi.

Philippi. Located in eastern Greece, the city of Philippi was the setting of the meeting of Paul and the slave girl, possessed with a “spirit of python,” in the Bible. Photo: Marsyas/CC by-SA 3.0.

Acts 16:16–24 is full of violence and exploitation. Byron notes that the slave girl in the story is not named; rather, she is known by her ability to tell the future:

We are never told the slave-girl’s name, only that she has a gift for fortune-telling. But this is not unusual, since enslaved human beings often lose the dignity of their name. In antiquity slaves were identified by their servile name and their inability to record their family name or tribe. Without a name to identify this girl, it’s possible she was better known by her unusual gift. Some may have called her “python-girl,” since what was important to clients was not her name, but the unusual gift attributed to a “spirit of python.”

Her owners exploit her fortune-telling ability. After Paul casts the “spirit of python” out of her, we are told that she loses this ability. However, beyond that—and her owners’ anger over this loss—we don’t what happens to her. Byron points out that her owners may have begun exploiting her in another way.

Apollo Temple. According to Greek mythology, Apollo killed the massive snake Python at Delphi. The temple for Apollo, set up at Delphi, housed an oracle possessed with the spirit of the god and able to see the future. In the Bible, the apostle Paul encounters a slave girl who is also able to see the future; she is said to be possessed with a “spirit of python.” Photo: Bernard Gagnon/CC by-SA 4.0.

Byron draws parallels between the story of the python-girl and those trapped in modern-day slavery:

The slave-girl’s situation is not all that different from those trapped in the modern slave trade, exploited by what they have, quite often their bodies. No name, no personal identity, no dignity. Like the python-girl in Philippi, they are viewed as less than people: commodities to be bought, sold, and traded.

The troubling elements in this passage can serve as a caution today. Byron concludes that although we don’t know what happened to the python-girl, her story can motivate us to help others who are still being exploited. To further explore the biblical episode of Paul and the slave girl from Philippi, see John Byron’s Biblical Views column “Paul, the Python Girl, and Human Trafficking,” published in the May/June 2019 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

——————Subscribers: Read the full Biblical Views column “Paul, the Python Girl, and Human Trafficking” by John Byron in the May/June 2019 issue of Biblical Archaeology Review.

Not a subscriber yet? Join today.

This post first appeared in Bible History Daily in May, 2019

Become a Member of Biblical Archaeology Society Now and Get More Than Half Off the Regular Price of the All-Access Pass!

Explore the world’s most intriguing Biblical scholarship

Dig into more than 9,000 articles in the Biblical Archaeology Society’s vast library plus much more with an All-Access pass.

Related reading in the BAS Library:

The Enigma of Paul: Why did the early Church’s great liberator get a reputation as an authoritarian? by F.F. Bruce

No biblical writer do we know more directly from his own writings than Paul. In those letters that are genuinely his, Paul’s personality comes across with unmistakable vividness. He regularly dictated his letters. As he dictated, his thoughts raced ahead of his words, and we may wonder at times how his amanuenses managed to keep up with him.

Biblical Views: Paul, the Python Girl, and Human Trafficking/strong> by John Byron

For some Bible readers, passages describing slavery sound like ancient history. The practice of kidnapping, selling, and exploiting human beings echo a bygone era. But, although no longer sanctioned by governments, slavery still exists. Today slaves are not identifiable by their skin color and ethnic origin.