In 1966, the Airborne Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, or ARVN, was formed with 12,000 troops. An elite unit, it conducted airborne assaults and airmobile operations throughout the war. Known for their distinctive red beret, called “Mu Do” in Vietnamese, the South Vietnamese airborne troops were assisted by U.S. advisers with airborne experience, who were members of Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) Team 162 and also known as “Red Hats.” Most advisers had served previously with the 101st, 82nd or 11th Airborne divisions.

The Vietnamese airborne troops and their advisers took part took part in many decisive battles of the Vietnam War, including at Hue and Dak To. During the Tet Offensive, airborne units were credited with killing over 2,000 enemy troops.

The Vietnamese troops and their advisers are honored today with a monument at Fort Benning, Georgia, which was built on the initiative of veterans of MACV Team 162 and unveiled in 2012. The monument pays tribute to them with a quotation from Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery on the valor of airborne forces: “What manner of men are these who wear the red beret? … They have jumped from the air and by doing so have conquered fear …. They have shown themselves to be as tenacious in defense as they are courageous in attack. They are in fact, men apart, every man an emperor.”

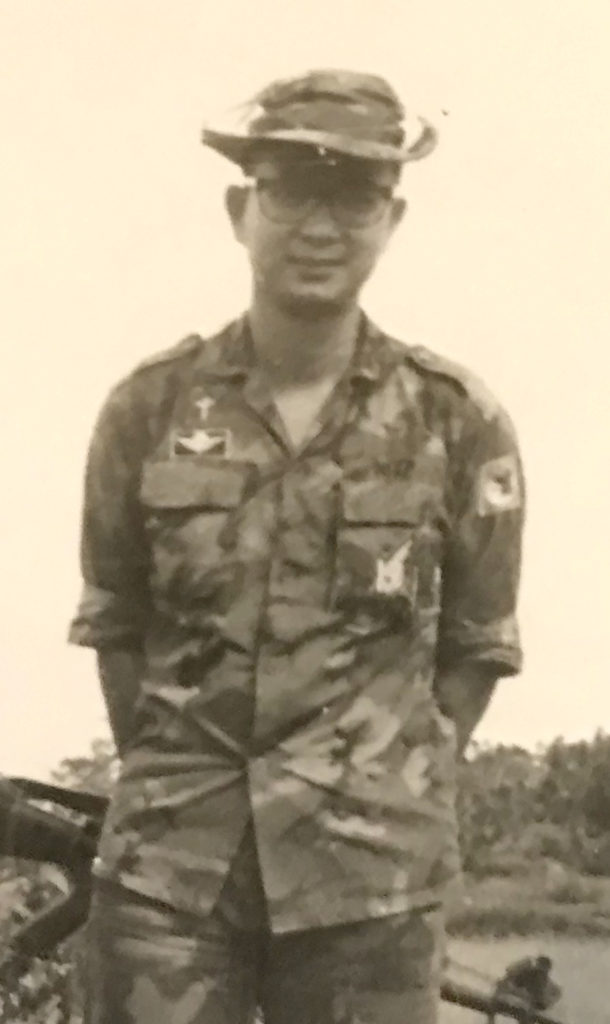

Vietnam magazine is honored to share the story of Dr. Nguyen Quoc Hiep, president of the Vietnamese Red Beret Association, who spoke with us about his experiences as an airborne officer during the Vietnam War and his subsequent journey to the United States, listed below.

Why He Fought

Most of us at the time had to join the military. We had no choice because of the North Vietnamese Army, which invaded the South. Communism is the worst regime in the world. They don’t respect the freedom and democracy of the people. They kill people for no reason. From 1954 to 1956, they had what they called the “Land Rice Field Reforms” — they took all the fields from the farmers and landowners and gave it to poorer people. But it was not the right thing. After that they killed the farmers — thousands of them. From 1956 to 1958, they didn’t like anyone speaking against their regime, so they killed people. Under communism, they didn’t allow us to have freedom. They only allowed people to have portions. For example, they only allowed people to have 15 kilograms [33 pounds] of rice a month. It was very difficult to live on that amount per month.

The communists received support from the Chinese government and also their allies, like Russia, at that time, and Eastern European countries like Romania, Czechoslovakia and Poland. At that time, those countries were under the communist regime so they provided them with everything including ammunition, tanks and missiles to attack and invade South Vietnam. The Viet Cong were not the North Vietnamese Army. They attacked us so we had to take care to fight against them.

The feelings of the villagers were sort of mixed. If they didn’t follow the communists, they would track down their family and kill them. If the people didn’t provide the communists with rice and money, they would kill them. So the villagers were afraid that they had to follow the communists. Most of the villagers who wanted to have freedom moved to big towns under the control of the [South Vietnamese] army. If they stayed in the small villages under the control of the communists, they had to provide them with rice and anything they needed.

Joining Up

I graduated from military medical school in 1968 and joined the airborne division in 1969. I served in the 11th Battalion as chief medical officer. After that I became chief medical officer of the 3rd Battalion. I served for one year on each battalion before I moved to the brigade. Then I became chief medical officer of the 2nd Brigade of the Vietnamese paratroopers. You had to graduate from high school to become an officer and attend a military school. Some people trained for two years, others for 18 months. Then they would select some for navy, air force, or army. Our families were very happy and supported us.

I lived in Saigon, but my battalion headquarters was in Long Binh, about 20 miles north of Saigon. Learning to be in the airborne forces wasn’t difficult. You had to pass three weeks of training. From 5 a.m. to 4 p.m. in the afternoon, we had training all day long. We ran for about 8 miles, then after that we had to train with equipment. After three weeks, we had to jump from airplanes to be certified as airborne soldiers.

I was young. I loved adventure. For the airborne, you can move from one town to another town, from one area to another. One day I would be in a town in the south. The next day I would be transported to a different town in the north, about 600 kilometers away. That is a lot of adventure! I needed to do that to help my comrades.

The most fun thing about being a paratrooper was jumping out of the airplane! The first jump was scary, but for the next one I was very happy and enjoyed it. In total, I made about 70 jumps in about seven years.

I was a medical officer, so I took care of wounded comrades-in-arms. I also took care of some of the civilians. When during operations we had to go to a village or town, some of the civilians needed medical attention. We took care of all of them.

Going Everywhere They Were Needed

During the war, we fought anywhere. Any battle where they needed us, we would go over there. In a difficult situation, we would go there to help and solve the problem in a heavy fight.

We had officers and many generals. We had five generals who commanded the Vietnamese paratrooper division. They have since mostly passed away. I remember Lt. Gen. Do Cao Tri, who stood out to me as one of the best commanders. He had very great courage and was very talented. But he died in a helicopter accident – it exploded in the middle of the sky.

I also worked with some of the American advisers. Most of them are now retired or have passed away because of their age. A couple of them have retired in Texas or New Mexico. The advisers fought side by side with our units and shared blood and tears with us.

During Operation Lam Son 719, we attacked a North Vietnamese base in Laos. I took part in this operation for almost two months. It was a very, very bloody battle on both sides. On the battlefield, we treated both Vietnamese and Americans. When the American advisers were wounded, we treated them and transported them to the American hospital faraway. Some of them went to the Seventh Fleet in the Pacific Ocean.

Most wounded I treated were Vietnamese paratroopers.

Leaving the Paratroopers – And Vietnam

We lost many friends. In total we lost more than 20,000 Vietnamese paratroopers during the war. And we had more than 20 American advisers who perished along with us.

I got out of Vietnam at the end of the evening of April 30, 1975, on a U.S. Navy ship. I went to America alone. A lot of relatives stayed behind, but now it’s been 46 years and they have passed away. I don’t have any chance to go back to my country because they are still under the communist regime.

People left because they wanted freedom. For example, the children of South Vietnamese officers were not allowed to go to school or have an education. They had to take low jobs because the communists would not allow them to work in higher positions. The communists only allowed people who followed them to get a higher education. Most of the children of officers of South Vietnam could not get into school, so that is one reason why families tried to escape from 1975 up to the 1990s. Most people escaped from Vietnam by boat, and many of them died in the open seas — for freedom and democracy.

Coming to America

I arrived in the United States in southern California, at a refugee camp in the Marine Corps base at Camp Pendleton. We stayed there in a tent for a couple months as refugees. Then I moved to New Jersey and got some medical training in the Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, area. Of course, I had a lot of difficulties [after arriving] because we are trained in French. After arriving in the U.S. we had to learn English. The language barrier was the most difficult problem. After a couple years we got used to the language.

In 1980, all former South Vietnamese paratroopers got together and organized. We call our group, “The Family of the Vietnamese Airborne.” People from all over the United States and the world joined us. Every year, we have a reunion meeting, depending on the people who want to volunteer to organize it. The last year before the pandemic we had a meeting in Orange County in southern California. It was our 39th reunion. The meetings were canceled in 2020 and 2021. We hope to have another meeting in 2022.