In 1926 author Walter Noble Burns published The Saga of Billy the Kid, the first book-length biography of the Kid since Charlie Siringo’s History of Billy the Kid, published in 1920. As Burns explained to readers, the unprovoked, sadistic murder of Englishman John Henry Tunstall on Feb. 18, 1878, was the event that kicked off the bloody Lincoln County War. Tunstall was killed while attempting to flee from a “posse” of at least two dozen men led by just deputized Jacob Mathews. The posse, little more than a lynch mob backed by Tunstall’s bitter business rivals Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan, included at least four notorious outlaw gunmen. Fleeing with Tunstall were Billy the Kid, Robert Widenmann, Richard Brewer and John Middleton. The men were driving a string of horses from Tunstall’s ranch on the Rio Feliz to Lincoln, as Tunstall wanted to save the animals from confiscation by the posse.

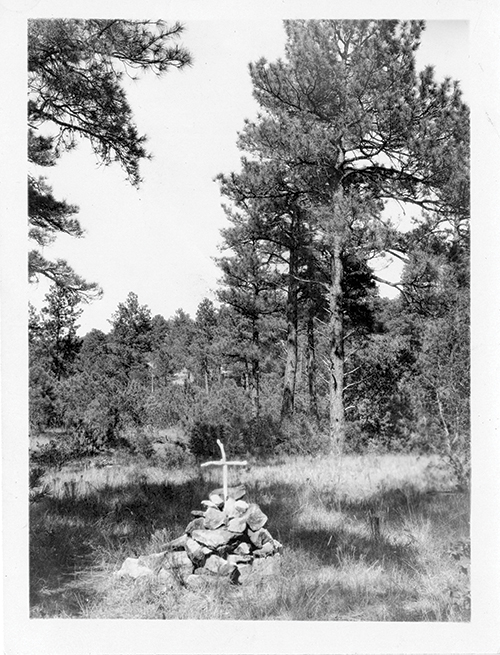

Motivated by the account of the murder in Burns’ book, two of Tunstall’s nephews traveled in April 1927 from England to Lincoln, N.M., to seek their uncle’s grave. They met with rancher George Coe and others still living in the Lincoln area who had known the late merchant and rancher. Coe took the pair to the spot where the Englishman had been murdered, and they marked it with a stack of rocks. Those interested in the history of the Lincoln County War owe a bouquet of thanks to Coe and the unnamed Tunstall nephews for their efforts.

That October rancher and New Mexico Representative James V. Tully, of Glencoe, wrote Paul A.F. Walter of the New Mexico Historical Society with a suggestion: “There should be a marker for the spot back of my ranch on the so-called Tunstall Trail, nailed on a juniper tree, to show where [Tunstall] was slain. This is now nearly forgotten.”

In the fall of 1929 Dr. William Alexander Osborne, dean of the medical school at the University of Melbourne, Australia, traveled to Lincoln to research the Lincoln County War. His interest, as he told an Associated Press reporter, “was aroused because Tunstall, the first victim of the range war, was an Englishman.” Stimulated by the publicity generated by Dr. Osborne’s visit, the U.S. Forest Service erected an official monument at the murder site that December. The site is thickly forested today, and it is challenging to mentally picture what it looked like on that fateful Monday when Tunstall was murdered.

The canyon where Tunstall was killed descends from a relatively flat plateau in the hills above and to the south of Glencoe, within the Smokey Bear Ranger District of the Lincoln National Forest. Calling it a valley is perhaps a better description. According to the Kid, in a sworn deposition provided to U.S. Department of Justice Special Investigator Frank Warner Angel, Tunstall’s party had just reached the mouth of the canyon, or the “brow of the hill” as Billy described it, when they sighted the posse riding “at full speed” behind them. Billy and Middleton were trailing some distance behind the other three, who were not riding together. Brewer and Widenmann were 200 to 300 yards to Tunstall’s left, off the trail. Tunstall was riding about 100 yards to the right of the trail, out in front of his horses, who were following the trail.

the unprovoked, sadistic murder of Englishman John Henry Tunstall on Feb. 18, 1878, was the event that kicked off the bloody Lincoln County War

Billy and Middleton raced forward to warn those riding ahead. The two had just reached Brewer and Widenmann when the posse commenced firing. The lead men in the posse, Tom Hill and William S. “Buck” Morton, were some distance in front of the main body. Billy said he, Widenmann and Brewer turned their horses left and rode “over a hill towards another, which was covered with large rocks and trees, in order to defend [ourselves] and make a stand.” Middleton galloped toward Tunstall, yelled a warning, and then veered left and joined Billy, Widenmann and Brewer.

According to the sworn testimony of posse member Albert Howe, Hill and Morton, having spotted Tunstall off on his own, galloped toward the Englishman, who stopped, turned and faced them. Hill called out for Tunstall to approach, assuring he would not be hurt. At the same time the pair stealthily drew their weapons. Tunstall rode closer, expecting to talk. Without warning, Howe said, “Morton fired and shot Tunstall through the breast, and then Hill fired and shot Tunstall through the head.” Howe’s testimony is thirdhand, however. The only witnesses were the killers themselves. But the evidence suggests certain conclusions.

Hill and Morton may have thought that with Tunstall positioned directly in front of them, it would be harder for any potential witnesses riding up from behind to know whether the Englishman had drawn on them. That was their alibi: He had shot first, and they had returned fire in self-defense. Someone also shot and killed Tunstall’s horse. Morton and Hill then dismounted and just had time to remove two cartridges from the Englishman’s pistol and drop it beside his body before the other posse members arrived on the scene. In a despicable act of mockery someone placed Tunstall’s hat beneath his dead horse’s head and beat the Englishman about the head with the butt of a gun.

That evening John Newcomb, Patricio Trujillo, Florencio Gonzales, Lázaro Gallegos and Ramón Baragón went after Tunstall’s body. “We could not get up the canyon in a wagon, so we packed it on a horse,” Gonzales recounted. “The body was lying by his dead horse’s head, with his and his horse’s head right together.” Newcomb added telling details. “The corpse had evidently been carried by some persons and laid in the position in which we found it,” he noted. “A blanket was found under the corpse and one over it. Tunstall’s overcoat was placed under his head, and his hat placed under the head of his dead horse. By the apparent naturalness of the scene we were forced to conclude that the murderers of Mr. Tunstall placed his dead horse in the position indicated, considering the whole affair a burlesque.…We found his revolver quite close to the scabbard on the corpse. It must have been placed there by someone after Tunstall’s death. We found two chambers empty, but there were no hulls, or cartridge shells, in the empty chambers; the other four chambers had cartridges in them.”

Billy the Kid and other self-appointed “Regulators” sought vengeance. On March 9 they killed Morton and another of the posse members along Blackwater Creek. On March 14 Hill took a fatal bullet while trying to rob a sheepherder’s camp. Then, on April 1, six Regulators, including the Kid, ambushed Lincoln County Sheriff William J. Brady and four of his deputies, killing the sheriff and Deputy George Hindman. There was no turning back. The Lincoln County War was in full swing.

A number of writers have wondered why Tunstall’s horse was shot and posed as it was. The answer is that the murderers knew about Tunstall’s deep love of horses, particularly a bay Thoroughbred named Colonel, who was in the string the Englishman been driving that day. Colonel was incurably blind. Tunstall had rescued the horse from the Fort Stanton butcher pen and tended him since. The gruesome death-scene posing of Tunstall and his horse was a final, depraved act of contempt.

On Feb. 18, 1978, the 100th anniversary of Tunstall’s murder, the Lincoln County Historical Society placed a second commemorative marker at the site, which is difficult to find. One can park within a half mile of it, but there are no markers to show where to begin hiking. Perhaps that too will be remedied someday. WW

For directions to the commemorative marker visit HMDB.org and enter the search term “Tunstall murder site.”